The Daiquiri

As America rocketed toward the end of the 1800s, new cocktails were being produced at a dizzying pace. Bartenders were looking to all types of new ingredients to add to old standbys, and to create new and unique drinks. Gins, vermouths, and champagnes were all trending dry, while liqueurs were being used to replace sugar. The world looked forward to new possibilities as the new century approached. Then right before the calendar changed, America ‘helped’ the Cubans fight off their old Spanish colonial oppressor, who had been raping and pillaging the natural resources of the Island. Once they gained independence, America stepped in to pick up where the Spanish left off. In 1898, an American mining engineer living on the island looked back a hundred years and created one of the history’s most iconic drinks. The Daiquiri.

Truth be told, it is likely that hundreds, if not thousands, of members of the British Royal Navy independently created the drink in the century before. In 1655 the British fought and won control of Jamaica, along with its highly profitable sugar cane industry – and rum came along in the bargain. The Navy had been supplying its sailors with ale (and its officers with brandy) as a potable liquid on voyages at sea (water would not stay drinkable for long in the hot ships hulls). But the beer took up a lot of room, and although it did much better than water, it tended to get ‘stinky’ after a couple months. Rum was the perfect replacement. It took much less room (and weight) and would last virtually forever. This was no white or aged rum, however – the rum was funky, and black, and called ‘Kill-Devil” for its taste, as well as what it did to the drinker. But it would still get you drunk. And at a time when most men who were not born of privilege had little in the way of career choices, rum made the Navy an attractive option.

Around the beginning of the 1800s, limes were brought on board to give the sailors some vitamin C to help ward off scurvy (it is estimated that 2 million sailors died from scurvy between 1500 and 1800). There are stories of Spanish Galleons floating in the ocean, entire crews having succumbed to the disease. Sadly, they didn’t know at the time that the cheaper and more abundant limes are very low in vitamin C, compared to oranges or lemons. The sailors, however, realized they could add the lime to their rum, toss in a little sugar, and create a nice little on-board drink. The pre-daiquiri.

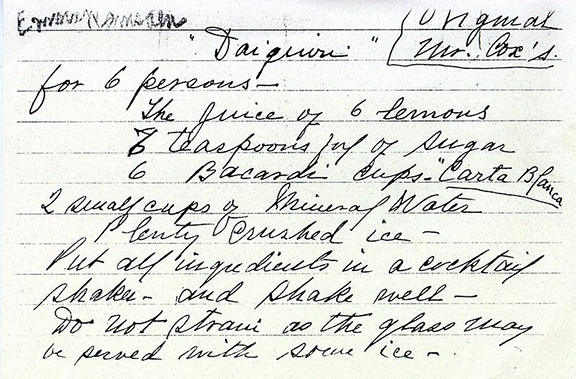

Back to our hero, Jennings Stockton Cox. While stationed in Cuba mining iron ore in 1898, so his often-told story goes, he hosted a party for visiting dignitaries. But to his horror, he found that he had run out of civilized liquor – i.e., gin. Rum was obviously in abundance on the island, but it was considered a poor man’s drink. Making do with what he had, he dumped some lemons, sugar, rum, and mineral water into a bowl, using a centuries-old punch ratio (One of sour, two of sweet, three of strong, four of weak), and found it to be a most agreeable drink. The Bacardi family had created a new way to distill and filter rum in 1862 on the island, so this was much closer to what we think of as white rum today. It was a huge hit. By accepted naming conventions, it should have been called a Rum Sour, but since he was staying in a small town named Daiquiri, next to Daiquiri Beach, and working at the Daiquiri Iron Mine, the name seemed obvious. He and his drink became local celebrities.

Juice of six lemons, 6 teaspoons of sugar, 6 Bacardi cups of ‘Carta Blanca’, 2 small cups of mineral water, plenty of crushed ice. Shake well.

It might have stayed local if not for Admiral Lucius W. Johnson, a U.S. Navy medical officer. He was accompanying Captain Charles H. Harlow of the USS Minnesota on a sightseeing tour of the historic Spanish-American War sites while visiting Guantanamo Bay. Cox hosted the pair and whipped up a few of his daiquiris – now served with lime and without the mineral water. Admiral Johnson was smitten, and upon returning to America, he began requesting that it be made by the bartenders at the Army & Navy Club in Washington DC. The drink was so popular that it became the official drink of the club, and the bar within the five-star platinum club was renamed the Daiquiri Bar and Lounge, as it is still to this day.

The drink grew in popularity during Prohibition, as Cuba billed itself as an alcoholic get-away during the Noble Experiment. Americans on the east coast flocked to Cuba to dine, dance, and daiquiri the night away. The drink was also helped by its unofficial Godfather, Ernest Hemingway. Starting in the 1930s, Hemingway would sail to Cuba to write – and to drink. One day he stumbled into a local bar, La Floridita, in Havana. looking for a place to use the bathroom. Hemingway was never one to pass up a bar, and the bartender Constantino Ribalaigua Vert was never one to pass up a patron. He offered Hemingway one of his daiquiris, which Hemingway liked very much, but offered a few modifications – double the rum and delete the sugar (Hemingway was an alcoholic and a diabetic). The modified drink came to be known as the Papa Doble Daiquiri, and Ribalaigua came to be known as “El Rey de los Coteleros,” – The Cocktail King of Cuba. In 1953, Esquire magazine named La Floridita the most famous bar in the world, the same year that its steadfast patron, Hemingway, received the Pulitzer Prize.

It is said it is easy to make a complicated drink, but it takes a stroke of genius to make a simple, perfect one. And there is not much simpler that a spirit, a sour, and sugar, shaken with ice. Soon other fruits were added, and the drink became buried in shaved ice. In 1938, Fred Waring introduced his Waring Blender to the world, shifting the drink to the frozen daiquiri. In the early 1970s, Dallas restaurateur Mariano Martinez created the first commercially viable frozen margarita/daiquiri machine, which was filled with pre-packaged mixes and all types of artificial juice and flavors, making continuous daiquiris on demand. The exquisite daiquiri suffered the fate of virtually all craft cocktails at the time and become a shadow of its former self.

Who cares, you may say. People love frozen daiquiris, you may say. YOU may love frozen daiquiris. Good. The best cocktail is the one you love. But if you want a real daiquiri, it needs to be prepared as a cocktail. Not because of nostalgia, you simply don’t get the same drink when frozen (same with margaritas, I’m sad to say). Your taste buds become numb from the ice, which makes it difficult to pick up alcohol and sweet. The sour is less affected, but to compensate, more sugar is added (and you tend to drink more since you can’t taste the liquor). Cold liquids do not allow odor to escape the drink as well either, which is important, since smell is an active part of taste.

So, if you are at the beach on a hot day, or standing in front of the BBQ in August, have a frozen daiquiri. Enjoy it. But occasionally, when you are at a good craft-cocktail bar, have one like it was intended to be.

Simple. Exquisite. Beautiful.

Cheers!

Bill

AotCB-027

Instagram@architecture_of_the_cocktail

Previous RUMinations in Architecture of the Cocktail:

The Golden Age of Cocktails, by Bill Stott

Hogo! by Bill Stott

How about a nice Hawaiian punch? by Bill Stott

“What one rum can’t do, three rums can” by Bill Stott

Yo, ho, ho, and a Bottle of Rum, by Bill Stott

Yo, ho, ho, and a Bottle of Rum – Part II, by Bill Stott

Spirits Up! Black Tot Day, by Bill Stott