Likely like most of you, I grew up thinking rum was always clear, and came in a clear glass bottle with a bat on the label. You made three things with it. You could get really fancy and make a daiquiri, you could add it to Coke, or you could add it to juice. There were exceptions; Long Island Iced Tea, Pina Colada, or a Tiki drink, but you only had one of those when eating out or going to a bar. Too complicated and too many ingredients!

That was no accident. Rum, like most food and drink associated with the American palate over the last 100 years, has raced to the average. In the 1800s, Americans drank a plethora of different beers. Ales, lager, pilsners, stouts, porters – but over the course of the 1900s, Anheuser-Busch drove the market to find the beer that appealed to the mean, ignoring the edges. The Bacardi family did the same thing to rum. Starting in 1862, they began filtering and blending different distillates (aguardiente and redistillado for those of you playing along at home) after the distillation process to find the smoothest Spanish style rum in Cuba, and then spent 100 years in an aggressive marketing campaign to convince us that this is what we really liked – even after they fled Cuba in 1960. I’m not really blaming them. Their tactics were aggressive to competitors, but we gladly guzzled beer and rum that tasted less and less like it did last year and the generation before that.

But in the last several decades we have been riding a craft beer rocket ship, where breweries are looking to older styles and techniques to bring different beers and flavor profiles to market. There is a similar movement in rum (and alcohols in general) that runs parallel. While some people like a summer shandy or fruit infused beer, some are drawn to the IPA, sometimes double or triple hopped – a beer not aimed at the widest population. In rums we see the renewed interest in Rhum Agricole (and its half-siblings Brazilian Cachaça and Arrack from Southeast Asia), a French style rum that produces rum directly from the pressed sugar cane, rather that molasses (a biproduct of sugar production), giving the rum a pronounced grassy, earthy, and some would say ‘funky’ taste. Most rum is made from molasses, the traditional way to make rum, and is characteristic of the older English and Spanish styles.

But as bartenders looked to the past to find historic recipes that they could dust off, they were faced with a problem. Many recipes from the “Bartenders Guide” by Jerry Thomas in 1862 through “The Savoy Cocktail Book” in 1930 referenced ‘Jamaican Rum’, a traditional English style rum. Which was virtually extinct. Thanks in no small part to the tedious research by David Wondrich and other mixology historians, there are now a number of rums on the market that echo the older production techniques, taste, and smell of those 19th century (and older) rums. Some call them ‘funky’ rums, some say they have ‘Jamaican funk’, but the name that seems the most appropriate is ‘hogo’ rums.

What is a Hogo Rum? The short answer references the old definition of pornography – you know it what you see it. Similarly, you know a hogo rum when you taste (and smell) it. The term hogo comes from the French term “haut gout”, referring to the taste of slightly tainted game meat – which may sound off-putting, but used to be considered a delicacy. Gaminess is the polite way to say it. “The fun and mystery of hogo is that it’s hard to define,” says Jim Romdall, the western brand manager for Novo Fogo cachaça. “If I could somehow say ‘rotten fruit’ and find the words to spin it into something positive and interesting, that would be it.”

Rum has had a long and interesting history, starting out as something so terrible it was “a hot vile liquor … called kill-devil” in the 1600s. In New England at the time of the Revolution, it was said you could identify rums, and even their quality by the stench (intentionally not using the word smell). The Hogo is, in essence, a reflection of the terroir – or environment the rum was created in. In much the same way that wine is affected by soil, climate, rainfall, etc., rum retains its Genius Loci, or spirit of its place. The soil, location, harvesting – and especially the still – all effect the rums’ smell and taste. A rum from Fiji is dominated by mace, while a Jamaican rum has toffee aromas and flavors. Both are hogo rums, but with different results.

The still is critical. The copper Pot Still (copper helps remove sulfur taste) is a single teardrop shaped still that was first used by the Scots in the 15th century. It is heated under its large flat bottom (historically by fire) and must be cleaned out after each distillation. It is simple technology, but the liquid is prone to burning from the direct heat source. And it wasn’t always cleaned properly, or at all, between batches, producing strong and unpredictable results. The Column Still, on the other hand, acts as a series of pot stills stacked vertically and operates continuously. It produces a cleaner product at a significantly higher volume but loses some of the taste and aroma that comes from a pot still. Its terroir. Its genius loci. Its hogo. Pot stilled rum retains more congeners – flavorful products of fermentation such as esters and aldehydes – than modern column stills.

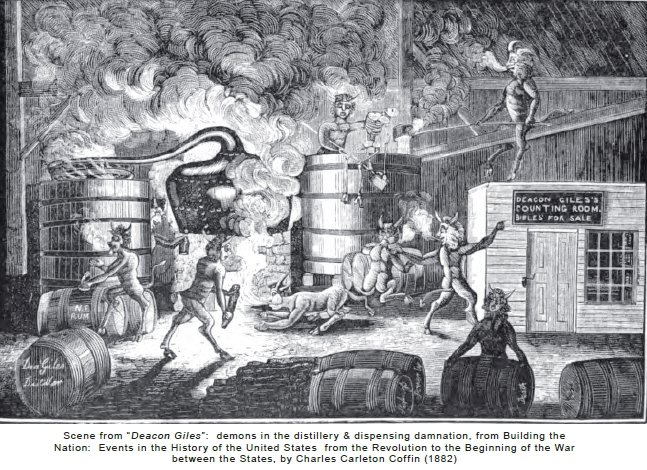

And let’s not forget the importance of the muck pit. When a still was cleaned out after distillation, the remainder left over in the pot (called dunder) was removed and dumped into a muck pit. In the 1800s, this was often an open pit in the ground. It would roil and boil as fermentation continued naturally. This dunder was added to the wash (the liquid just prior to fermentation – like wort in brewing) to flavor the wash or jump start the fermentation process. There are numerous examples in the early days of dead bats or rotting goat carcasses being tosses in as well to get the taste and smell juuuuust right. These techniques are still used today (minus the dead animals) to help the rum establish its hogo. So why would you want to filter all that work out?

Now, your reaction may be, why on God’s green earth would you want to drink something like that? Which is a funny question, because that is exactly what my wife asks (along with a clenched up face) after I give her a taste of my IPA. Some hogo rums are an acquired taste, like a highly peated Scotch. But some are really wonderful. And I can tell you that cocktails created in the 1800s and even up through the Tiki revolution ending in the 1960s are mere shadows of their former glory when made with a bland, clear (or even a bland aged) rum. So, when you see a recipe that calls for a Jamaican rum, reach for a bottle of pot stilled Smith & Cross. Or Rhum Agricole. Or maybe even Arrack. It won’t taste like a rum and Coke, but if you really allow it – you will encounter complexity, depth, and flavors you cannot find anywhere else.

Cheers!

Bill

AotCB-024

Instagram@architecture_of_the_cocktail

Other RUMinations in Architecture of the Cocktail:

HAVE YOU EVER HAD A REAL DAIQUIRI? by Bill Stott

The Golden Age of Cocktails, by Bill Stott

Hogo! by Bill Stott

How about a nice Hawaiian punch? by Bill Stott

“What one rum can’t do, three rums can” by Bill Stott

Yo, ho, ho, and a Bottle of Rum, by Bill Stott

Yo, ho, ho, and a Bottle of Rum – Part II, by Bill Stott

Spirits Up! Black Tot Day, by Bill Stott