RICHIE’S REPRISAL: Thoughts from A Pallid Pilgrim

So You Wanna Be a (Christian) Rock ‘n’ Roll Star

by Rich Horton

FALLEN ANGEL: The Outlaw Larry Norman. The Unauthorized Documentary

a Bible Story by David Di Sabatino

Jester Media, 2009

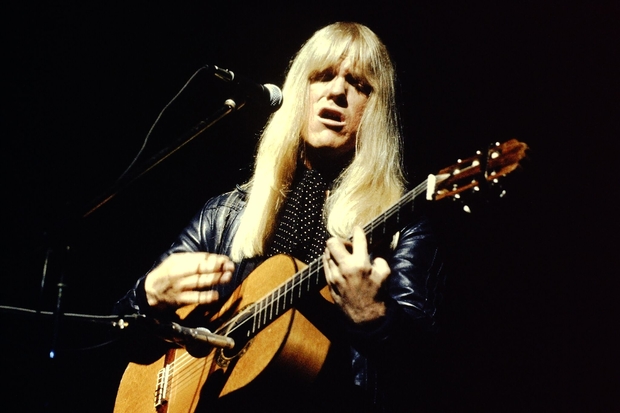

You may not have heard of Larry Norman, a singer-songwriter who died a little less than two years ago, but who was at one time considered the Bob Dylan-Beatles-Rolling Stones of the nascent Jesus Movement of the late 1960’s and early ‘70s. To this day, he is still widely considered the Founding Father of Jesus Rock, a genre that now goes by the white-bread name of Contemporary Christian Music, or CCM.

I’ve been fascinated by Larry Norman ever since early 1971, when as a college freshman I stumbled on his seminal Jesus Rock album, Upon This Rock (Capitol Records,1969). For a newly-christened Jesus Freak like me – a guy who’d cut his teeth on The Beatles, had thoroughly consumed virtually every important rock album of the Sixties, and had played in rock groups since the age of 13, but who had recently joined the ranks of the Jesus Movement –  I was thrilled and delighted to find a genuine rock artist who was singing about Jesus. Unlike some previous so-called contemporary Christian singers, Larry Norman was an authentically talented singer-songwriter with solid rock credentials (his previous band, People!, from San Jose, had rocked the charts only 1-2 years earlier, with their psychedelically-tinged hit, “I Love You”). And Norman himself had undeniable charisma, he was highly articulate, and his songs were populated with Dylanesque wordplay and allusions to history, literature, and pop culture with none of the “church-talk” I’d come to associate with the kind of Christian music for today’s young people (but written by 40-year-old record producers) that religious youth leaders had tried to pawn off on my generation for several years. And as the ‘70s dawned and many of the children of the Sixties were embracing a radically new kind of counter-cultural Jesus, it was clear to me that Larry Norman would be a musical and intellectual force to be reckoned with in the years to come.

I was thrilled and delighted to find a genuine rock artist who was singing about Jesus. Unlike some previous so-called contemporary Christian singers, Larry Norman was an authentically talented singer-songwriter with solid rock credentials (his previous band, People!, from San Jose, had rocked the charts only 1-2 years earlier, with their psychedelically-tinged hit, “I Love You”). And Norman himself had undeniable charisma, he was highly articulate, and his songs were populated with Dylanesque wordplay and allusions to history, literature, and pop culture with none of the “church-talk” I’d come to associate with the kind of Christian music for today’s young people (but written by 40-year-old record producers) that religious youth leaders had tried to pawn off on my generation for several years. And as the ‘70s dawned and many of the children of the Sixties were embracing a radically new kind of counter-cultural Jesus, it was clear to me that Larry Norman would be a musical and intellectual force to be reckoned with in the years to come.

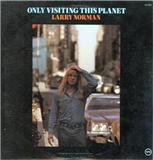

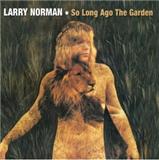

After that initial encounter with Norman’s first album, I saw him perform a dozen times or so. I devoured every article and interview I could find on him, and in the nearly 40 years since then, I’ve replaced my copies of  Only Visiting This Planet (Verve, 1972) and So Long Ago The Garden (MGM, 1974) numerous times. To this day, I still consider both albums as high points of ’70s rock, religious or secular.

Only Visiting This Planet (Verve, 1972) and So Long Ago The Garden (MGM, 1974) numerous times. To this day, I still consider both albums as high points of ’70s rock, religious or secular.

But despite my fascination and fan-love, I began having questions about Norman, starting in 1972 when I worked as Managing Editor of “The Hollywood Free Paper,” an underground newspaper for which Larry had previously been a columnist. Although I sometimes questioned the paper’s direction, I had great respect for the integrity of Duane Pederson, the paper’s editor and publisher. And when I asked Duane why we didn’t publish Larry’s column anymore, it was a true indication of Duane’s integrity that he refused to bad-mouth Larry. Instead, he confirmed Larry’s “genius” but made some vague comments that suggested to me he’d felt wounded by Larry in some way. And it was further telling to me that Norman was no longer invited to perform at the regular concerts our newspaper sponsored, nor were his records played on Pederson’s syndicated radio program.

And, then in the following years, although I remained a Norman devotee, I kept finding myself bothered by a number of nagging questions:

why did Larry Norman keep embellishing (and even dramatically changing over time) the details of his childhood and other facts of his life?

why did he leave in his wake a trail of alienated admirers that included wives, his best friends, and the people he’d worked with, both managers and other artists?

why did he always characterize himself as a victim and a martyr of the Christian establishment, when it was clear he was widely respected and loved? (contrary to his claims, not very many Christian stores banned his records . . . .but he used the one or two who did to “prove” there was mass conspiracy against him, and it played into Larry’s campaign of portraying himself as a misunderstood genius),

why did he take credit not only for his own success but also for that of other talented artists who worked with him, as if it were solely based on his influence that they’d succeeded?

why did he publicly attack anyone who was less than positive in their assessment of him, and misrepresent their comments and actions as proof of an agenda against him?

why did he continue to name-drop any famous artist/writer/thinker whom he’d ever met, no matter how incidentally, and then present them as part of his in-crowd, particularly when it was clear that most of the people he mentioned, never mentioned him?

why did all his albums include a self-published interview with himself that was implied to be the work of a 2nd-party objective journalist?

why was he unwilling to be in a community of people (a church, a fellowship, an organization) where he would be held accountable for his words and actions?

why did he – after his very public denunciation of the Viet Nam War – publicly endorse Oliver North, the disgraced warrior who ran an illegal and “secret war” against Nicaragua out of the White House basement during the Reagan administration.

and, finally, why was his music so increasingly insipid, clichéd, and banal following the artistic pinnacle of his so-called trilogy: Only Visiting This Planet (1973), So Long Ago the Garden (1974), and In Another Land (1977)? (Larry’s own explanations for his erratic behavior and musical output ran a gamut, suggesting that he was simply paranoid, mentally imbalanced, or both.)

and, finally, why was his music so increasingly insipid, clichéd, and banal following the artistic pinnacle of his so-called trilogy: Only Visiting This Planet (1973), So Long Ago the Garden (1974), and In Another Land (1977)? (Larry’s own explanations for his erratic behavior and musical output ran a gamut, suggesting that he was simply paranoid, mentally imbalanced, or both.)

At long last, many of these questions are answered in David Di Sabatino’s documentary Fallen Angel: The Outlaw Larry Norman. The film – which is replete with long-unseen footage from the early days of the Jesus movement and from Norman’s live concerts and appearances, and which is augmented by new recordings from former Norman protegé Randy Stonehill – presents the “other side” of Larry’s life as told by the people who knew him best: former band mates, wives, best friends, business associates. And over and over, they all repeat a similar story – of their own love for and devotion to Larry, followed by their utter astonishment when he subsequently vilified them in the press, on stage, and in the lyrics of his songs. And more times than not, Larry’s “version” of the events in question turn out to be at complete odds with what others close to the situation report as the truth.

Fallen Angel also raises newer questions when it introduces us to an Australian boy in his late teens who bears a strong physical resemblance to Larry Norman, and whose mother claims is, indeed, the out-of-wedlock son of Larry Norman. The boy and his mother have agreed to undergo DNA testing to prove their claims. While the Norman family to date has refused the testing, it is ironic that in the days leading up to Larry Norman’s death, and despite his denial of paternity, he nevertheless included the boy in his will. Strikingly, however, in a similar manner to the way he treated so many former friends and associates, at the last moment Larry changed his will to substantially reduce the amount he’d initially left to the boy. It’s just one more event – and perhaps the most heartbreaking of them all – that makes you scratch your head about what really motivated Larry Norman.

I still consider myself a Larry Norman fan, but I have been amazed by the astoundingly rabid reaction to this documentary by the Larry Norman fan-base, which, in some respects, sometimes seems cult-like. They have screamed that Fallen Angel represents a posthumous smear campaign against Larry Norman. It’s ironic that that those who feel that Larry showed them the light do not want the light shone on their hero, ignoring the fact that when Norman was alive, he was invited, yet refused to participate, in the documentary’s making. And after the film was completed, the Norman family unsuccessfully sued to block its release. (In fact, the story of director David Di Sabatino’s continued dealings with the Norman family, who have verbally attacked the filmmaker in print and on the web, could make an interesting documentary in itself.)

While the Norman family is correct that the lion’s share of the content of Fallen Angel comes from alienated friends and associates of Larry Norman, it is also true that those voices are long overdue, particularly given all the innuendo and attacks on them, which were perpetuated by Larry Norman himself over the years. Certainly, viewers of the documentary can judge for themselves who’s telling the truth, and whether any of them has anything to gain from lying. Either way, it is refreshing, at long last, to get another side to the stories Larry told about them over the years.

Despite the attacks on their characters, what is perhaps the biggest surprise of the Fallen Angel, however, is how many of these people – particularly Larry’s former best friend, Randy Stonehill – still deeply love and have forgiven Larry. Now, THAT is amazing grace.

By definition, because no one is perfect, anyone who has a gift will imperfect. But that doesn’t preclude the possibility that others can be touched or blessed by the gift, no matter how imperfect the bearer of it. However, the questions I raise here (and the questions raised by the documentary I review) are not whether human beings, or even Larry Norman is or is not perfect. The bigger point is whether we maintain certain expectations for those who claim to speak on God’s behalf. And when they fail, as they surely will, what do we do about it? Do we sweep unseemly incidents under the rug and excuse them just because of human imperfection or flaws? And what about cases when an individual refuses to acknowledge legitimate concerns about his or her failures and even attacks the individuals who raise them? Certainly, we all need understanding and grace. However, to my knowledge, as someone who briefly “ran” in Larry Norman’s sphere and followed him closely, I have never seen any evidence that he ever admitted to ANY imperfection or flaw, even while publicly rebuking others for their imperfections.

Ultimately, Fallen Angel cannot answer the biggest question: was Larry Norman’s faith and message merely a convenient niche to further his aspirations, or was he a genuine-though-deeply-flawed messenger of God’s grace? Those closest to the man don’t all agree. But for the legions of followers who knew Larry only through his music and found it a vehicle of grace and forgiveness, it is obvious that they subscribe to the latter view.

Rich Horton

*****************************************************************