There are few spirits with more mythology and lore than absinthe. Loved by many, loathed by as many, and known in name only to the majority. Absinthe began as a medicine, became a popular drink, obtained a cult-like status, was made illegal, and has a new life thanks to the rebirth of the craft cocktail renaissance.

Absinthe or Absinthia

BACKGROUND

For as long as there have been people, there has been the desire to find cures and medicine for the inevitable problems and injuries that occur. Herbs, roots, and plants have held hope for relief – and thanks to thousands of years of trial and error, many actually perform well. Of those, anise, fennel, and wormwood have been especially popular in medicines wherever they are naturally occurring. Anise is considered a carminative (decreasing bloating and gas in the digestive tract) and an expectorant (thinning mucus to allow for more productive coughing) and is widely used today in the treatment of cough, asthma, and bronchitis. Fennel is an anti-inflammatory, it promotes heart health, and is considered antibacterial. And wormwood is used for treatment of stomach ailments, fever, liver disease, muscle pain, – and of course increases sexual desire. Pretty potent mixture.

For centuries these three have been incorporated into a multitude of tinctures and medicines. In the Eighth and Ninth Century Arab alchemists began distilling alcohol in an effort to make perfume. They discovered that alcohol has an amazing ability to pull smell and flavors out of everything from flowers to roots to herbs. By the Tenth Century, European alchemists had shifted their attention to medicines, and their efforts were rewarded with tinctures that not only pulled the essence out of the materials they were macerating (the alcohol acts as a solvent, extracting flavor, color, and aroma) but thanks to the high alcohol content, they were able to stay shelf-stable far longer than the plant or root would. Then in the Eighteenth Century is seemed like every monastery in Europe and the Middle East began making what would become the plethora of liqueurs, aperitifs, and digestifs, utilizing the vast amount of herbal trial and error that had occurred over the previous millennium.

HISTORY

Absinthe was created in the late 1700s in the canton of Neuchâtel in Switzerland. Liqueurs had not yet begun their transition from medicine to alcoholic beverage across Europe and Asia, but soon anise based alcohol/medicine was everywhere – ranging from Arak in the Middle East, Ouzo in Greece, Sambuca in Italy, Aquavit in Scandinavia, and Absinthe across Europe. According to lore, absinthe was created by Dr. Pierre Ordinaire, a French doctor living in Couvet around 1792 and devised as a medicinal elixir. Major Dubied acquired the formula in 1797 and opened the first absinthe distillery named Dubied Père et Fils in Couvet with his son Marcellin and son-in-law Henry-Louis Pernod. The elixir was given to French soldiers to help prevent malaria in Algeria, and they brought back a newfound appreciation for the spirit. It became so popular that by 1860, 5pm in bars, cabarets, and bistros became known as l’heure verte (“the green hour”). It was popular with the rich, as well as the starving artist, and traveled across the world.

It became a popular drink by itself or with water (water pulls much more of the flavor out than can be tasted in just the spirit), as well as a component in the exploding world of the cocktails. Its most historic and famous cocktail, the Sazerac, was created in 1838 by Antoine Peychaud in his apothecary in New Orleans and named after his favorite French brandy, Sazerac-de-Forge et fils. Along the way, the cognac was replaced with rye (many claim it was due to the world-wide cognac shortage resulting from the grape vine killing phylloxera in the 1870’s), and in 1873, a dash of absinthe was added by bartender Leon Lamothe – creating the cocktail we know it as today.

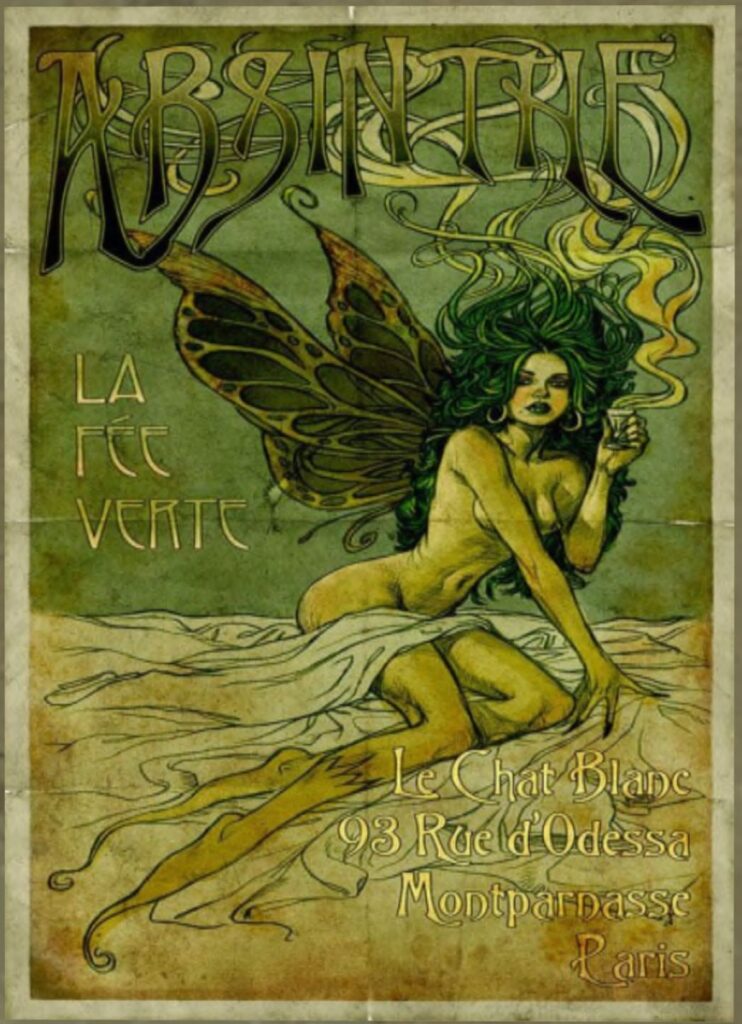

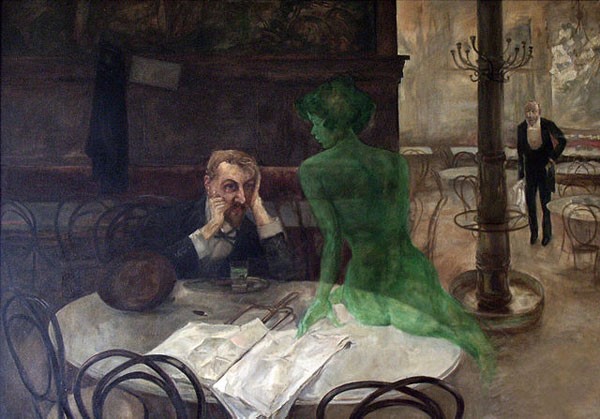

The Old Absinthe House in New Orleans began selling absinthe ‘Parisian style’ and the drink became popular with fans including Mark Twain, Oscar Wilde, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Parisian Style, or French Style, consists of pouring or dripping water over a sugar cube sitting on a slotted spoon, slowly changing the color and clarity of the absinthe below. Absinthe is typically green from the bottle, due to the green anise, but clouds and turns white when water is added. This color, and the (unfounded) myth that absinthe would make you hallucinate and see “la fée verte” or “The Green Fairy” propelled the drink’s popularity. The spirit gained a reputation as a hallucinogenic spirit, and quickly became a favorite of the bohemian artists who used it for inspiration. There is no basis for the claims of it being mind-altering, but absinthe has a very high alcohol content and all that popularity resulted in an untold number of drunken abuses. And no doubt countless evenings where overly imbibing artists saw things that weren’t there.

By the beginning of the Twentieth Century the spirit began to be banned across the globe, (the beginning of a global temperance movement) beginning with Brazil and Belgium in 1906, the Netherlands in 1909, Switzerland in 1910, the US in 1912, and France in 1914.

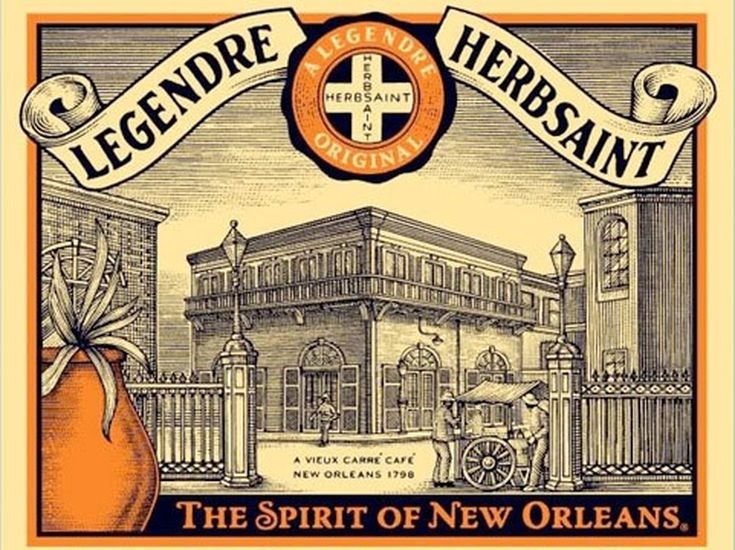

The loss of absinthe was hard felt in New Orleans, where the Sazerac had become the cocktail synonymous with the multicultural city – French absinthe, Creole bitters, and American whiskey. As soon as America emerged from Prohibition, a replacement was needed. Herbsainte was created by the Sazerac Company as an absinthe substitute and became the de facto official ingredient of the Sazarac for almost 80 years. In 2007 the ban was lifted, and Lucid Absinthe became available in the United States, and soon many historic distilleries were being dusted off, in addition to a plethora of new craft distilleries making their own spirit – many with a local emphasis on vernacular herbs and roots.

TASTING NOTES

Lucid Absinthe

62% alcohol by volume (124 proof)

Color: Faint yellow green. Clear

Nose: Strong fennel and anise/black licorice smell.

Taste: This is a hot spirit. Be prepared. The anise and fennel are upfront and strong but fade into a complex earthy and grassy mid-drink. The herbal spice and anise stay with you for an exceedingly long finish. The sips become progressively smoother as you move through the glass, but make sure you have plenty of water handy. Drink modifiers and bitters are referred to as spices in cocktails. In that vein, absinthe is more like curry. Rich and bold in flavor – but a little goes a long way. I have had a number of Parisian Style absinthe drip drinks, and the spirit really needs the water to open the drink up and show you the complexity that lies within. I still hate black jellybeans but have come to really enjoy the complexity of absinthe and what it brings to a cocktail.

Herbsainte

50% alcohol by volume (100 proof)

Color: light amber with a touch of green. Clear, but darker than the Lucid

Nose: Fennel and anise/black licorice smell, but much less than the absinthe. There is a slight salt aroma as well.

Taste: The name Herbsainte is a play on the French pronunciation of absinthe – ‘absente’. After the Lucid this seems absolutely mild in comparison. The anise and fennel are still there, but the lighter anise flavor is dominant and It really never seemed to evolve into anything other than what it is. A good, and well made, replacement for true absinthe.

HOW TO USE IT

Many drink absinthe Parisian Style, especially in craft cocktail bars with elaborate absinthe fountains. A large glass vessel is filled with ice and as the ice melts, the cold water slowly drips over a sugar cube and through a slotted absinthe spoon into the glass below. The traditional absinthe glass has a bulb at the bottom, used as a measuring device for the proper amount of the spirit, and the drinker waits until the sugar has fully dissolved before drinking. This method allows the drinker to sip it once the sugar has dissolved or allow more cold water to be added to dilute it further. The spirit goes through a ‘louche’ effect, where the clear, colored absinthe turns cloudy white. It begins slowly as water is added (reinforcing the ‘dancing fairy’ myth) until it is fully white, thanks to anethole, an essential oil found in high concentrations in anise seed. Oils dissolve in alcohol easily, but when the high alcohol content of absinthe drops, the anethole begins to separate from the alcohol, forming the white cloudy appearance.

If you want to try this at home, but don’t want to buy a fountain, empty half the water out of a water bottle and freeze it. Once frozen, fill the bottle with cold water and let it sit for 10 minutes or so. Place a shot of absinthe in a glass and set a sugar cube on a fork above the glass. Partially unscrew the water bottle cap and let the ice-cold water drip onto the sugar cube. When the cube is dissolved, give the drink a few stirs with the fork and you are done. It should have separated prior to the cube totally dissolving once the ratio of water to spirit hits the right point. You don’t really need the sugar cube, but just like in an old fashioned, a little water and a little sugar open up the spirit and can reveal flavors that are not apparent straight (this is why many serious bourbon or whiskey drinkers will add a few drops of cold water – I use three) to a neat pour.

Beyond the absinthe and water, most cocktails use absinthe very sparingly. Some treat it as a bitter and measure in dashes or drops (a la Louisiane. McKinley’s Delight, Chrysanthemum). Rinses were very popular in classic cocktails (Sazerac, Corpse Reviver #2) where a small amount of absinthe is placed in a chilled cocktail glass, and it is turned to layer the spirit onto the entire surface. The excess is pouted out and the drink is then strained over the absinthe. The method has been given a new, hip overhaul by using an atomizer and laying a fine mist of absinthe across the surface of the drink at the end – greatly enhancing the aroma.

Or go all in as Earnest Hemmingway did in his Death in the Afternoon, where a whopping 1 1/2oz of chilled absinthe is poured into a champagne flute and topped with chilled champagne. Trust me – there is a reason for the name. Especially if you decide to go for a second.

Cheers!

Bill

AotCB-045