Here in Nebraska, and specifically in Nebraska City, we are in the middle of the 52nd annual Apple Jack Festival. It is a yearly celebration of the apple harvest, and a signifier of the transition from summer to fall – just as we have been celebrating for centuries in America. Apples have been an important part of the history of the United States since the beginning – but it strikes me as humorous that the Apple Jack Festival, a family-friendly two week celebration has it roots (and fruits) in alcohol.

As I mentioned last week, Johnny Appleseed, aka John Chapman, is important to American history because he encouraged the spread of westward expansion by planting apple orchards across Illinois, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. This was done in advance of settlers expanding into the new territory. The apples were grown to becomes cider, a mildly alcoholic drink that could be kept all year to provide a safe source of liquid to drink. But Chapman was a latecomer to the apple-spirit party.

North American apple harvests began in 1609 in Jamestown, Virginia, from seeds and cuttings brought over from England. But they were not for eating. The bitter fruit was destined for one thing. Cider. It was consumed all day long, even by children and infants – along with beer – but especially in the mornings and during the workday. At the time the cider may have been as low as 2-3% alcohol. Low enough to allow you to work, but not enough to blow off steam with your friends in the tavern. So, cider begat hard cider, which begat apple brandy and applejack.

When you think of apple spirits in America, your search is not long. The Laird family has been distilling apples for over 300 years. Scotsman William Laird settled in Monmouth County New Jersey in 1698 and immediately began producing apple brandy. Sometime around 1760, William’s great grandson, Robert Laird, friend of a young George Washington, was talked into handing over the family recipe for their applejack spirit. Washington was quite a businessman, and operated a distillery on his Mount Vernon estate, and he began making his own applejack for personal use. To this day, Washington remains the only non-family member to have ever seen the recipe. In 1780, Robert incorporated the Laird Distillery, becoming the first commercial distillery of any kind in America. New Jersey was the breadbasket for the colonies at the time and had immense apple orchards. By 1840’s, the Laird family purchased a 22-acre site in Scobeyville, New Jersey, for the family residence and distillery. The home still stands, but it has been converted to the businesses’ office today.

So what exactly is applejack – or Jersey Lightning as it used to be called – and what are they celebrating at the Apple Jack Festival? You can make brandy out of virtually any fruit. Georgia didn’t become the peach state to make peach cobbler after all. You first ferment the fruit by adding yeast. The short version is that yeast eats the sugars in the fruit and converts it to alcohol (ethanol). This is basically wine at this point (same process for beer and mead). But there is a limit to the concentration of alcohol naturally, so it needs to be distilled. The traditional method of distillation uses heat to separate the alcohol from the rest of the liquid, since alcohol converts to steam at a lower temperature than water. Methyl alcohol converts to steam first, followed by ethyl alcohol. In steam distillation, the methyl is not captured – since it is essentially poisonous. This is what rubbing alcohol is made from. The ethyl however – that’s the good stuff. When you start with wine – this distillation creates brandy.

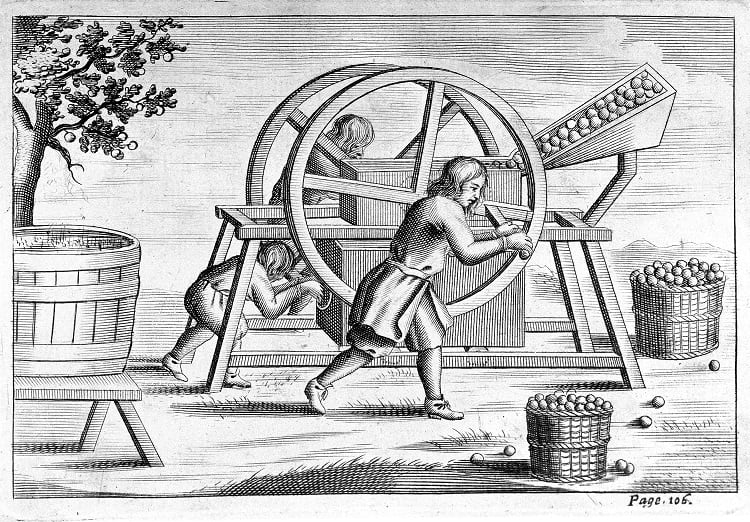

Applejack, on the other hand, relied on freeze distillation – called jacking – of cider. A vat/tub/barrel of apple cider would be left outside overnight when temperatures dropped below freezing, and the water within would crystalize and be easily removed the next morning – resulting in a higher concentration of alcohol. This was done over a series of days, removing the ice at intervals. This is a low-tech approach to distillation and no special equipment is required. It is pretty easy to do at home as well. But it cannot reach the same concentration as steam distillation, as the mixture becomes more difficult to freeze as the alcohol content goes up.

One other drawback – the freezing does not remove the trace amounts of methyl, so you end up drinking that too. This can lead to what is called ‘apple palsy’ – an intense hangover or if enough is drunk. For this and other reasons, applejack no longer uses freeze distillation, and instead relies on traditional steam distillation. So you are safe – but if you drink too much you will still get a hangover.

In the end, applejack is a wonderful and underappreciated hard spirit. It pretty much disappeared during the vodka invasion of the 70s and 80s, but luckily the Laird family is still producing it (the only applejack distillery still operating in America), and the craft cocktail renaissance of the last 20 years has embraced it. It has a wonderful crisp apple undertone, without being too apple-y. Similar to the sugar or oak undertones of a good bourbon. Fully worthy of the parades and family fun at the Arbor Day Apple Jack Festival in Nebraska City.

Cheers!

- Bill Stott