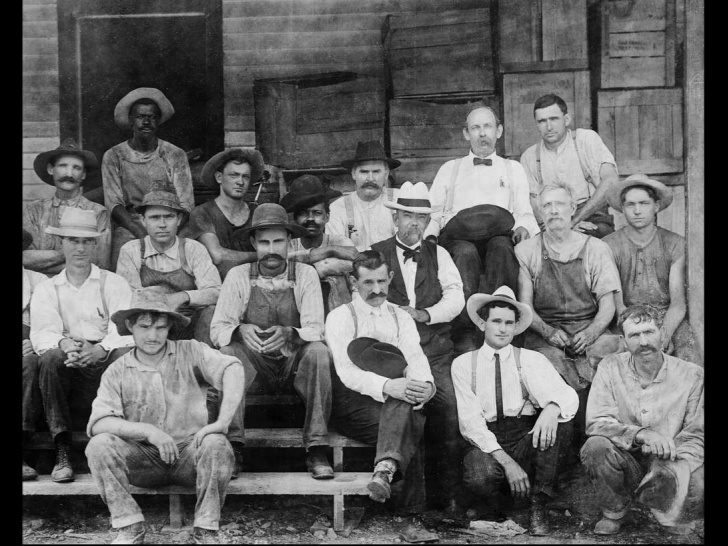

Rare photo of Jack Daniel (middle, white hat) next to George Green, son of Nathan ‘Nearest’ Green taken around 1900.

Sometime around 1855, a young 6 year-old named Jasper went to work for a preacher, grocer, and landowner in Lynchburg, Tennessee named Dan Call. His mother had died from complications resulting from his birth, and there were nine other young mouths to feed. Jasper was a hard worker, and showed special interest in one of Call’s other business ventures. The preacher also had a side business – he distilled whiskey. And good whiskey at that. The legend has it that the good Reverend Call was so impressed with the young boy’s work ethic and interest in distilling, that he took him under his wing and taught him everything he knew about the art of making whiskey. But as is often the case, the truth is more interesting than the legend. The preacher was not the real distiller. A young slave was responsible for the fine whiskey that Call sold on the side, and was the person who taught Jasper how whiskey was made. The relationship between the black mentor and white mentee resulted in a lifelong friendship. It also changed the arc of distilling in the state. The slave, Nathan ‘Nearest’ Green, is credited with developing the Lincoln County Process, a charcoal filtration technique that creates the distinctive Tennessee whiskey taste. And young Jasper Newton Daniel, or Jack as he was known to his friends, went on to create one of the best selling whiskeys in the world. But this story is not about a white free man taking credit for something an unnamed slave created. This is the story of a lifelong friendship, and two families, one white and one black, who remain friends to this day. But sadly, it is also the story of how we, as consumers, were happier to believe the legend than the truth.

Cocktail history, like history in general, is written by the winners. The first one to print a recipe typically became the one credited with the creation of a cocktail or technique. This is especially difficult for someone who was not considered a whole person and was forbidden to read or write. It shouldn’t surprise anyone, but slaves had a deep and important relationship with the distillation of whiskey in America. Like their peers in the Caribbean, using slaves to harvest sugarcane and distill molasses into rum, wealthy American landowners weren’t actually out there doing the hard work. Especially in the South, slaves made up the bulk of the labor force, and were often integral to the skilled roles in the process. But Jack Daniel was always happy to credit ‘Uncle’ Nearest. Green and his descendants were mentioned almost 50 times in the official biography of Daniel, “Jack Daniel’s Legacy,” printed in 1967. The story relies on interviews and history from the Daniel family – all willing to talk about the role Uncle Nearest played in the success of the Jack Daniel’s brand.

Outside Lynchburg, virtually no one had ever heard of Nathan Green. The descendants of Green and Daniel remained close – played with each other, ate with each other, and worked with each other. The distillery never shouted the story from the rooftops, but they never hid from the truth either. That began to change in 2016, as the company approached its 150th anniversary. They pushed out several historical talking points to the press – one of them highlighting the relationship between Green and Daniel. This piqued the interest of a New York Times reporter originally from Tennessee, Clay Risen. Risen had grown up in Tennessee – and grown up with Jack Daniel’s Old No. 7 whiskey – but had never heard the true origin story of the iconic brand. He had even read the 1967 biography on Daniel. He, like most, read it and still never made the connection of Uncle Nearest the slave. He traveled back to Lynchburg to investigate the story further and ended up writing a New York Times story published on June 26, 2016 that changed everything.

This started a ball rolling across the globe, where Fawn Weaver picked up a copy of the New York Times in Shanghai and read about the slave who taught Jack Daniels how to make whiskey. Weaver is an African-American author and historian, and she immediately became obsessed with the story. As she put it, hundreds of thousands of nameless slaves toiled their entire lives only to have a white owner take credit or benefit from their work. And here was a story – possibly for the first time – when that slave had a name and whose accomplishments were not coopted. She soon found herself in Lynchburg, TN, and began talking to relatives of both the Green and the Daniel families. She quickly gained their trust, ensuring them that she was mostly interested in the relationship between the two men, and the entire community opened their scrapbooks and keepsakes and produced thousands of pieces of evidence. As she puts it – this story became a community project.

In the 1967 biography, Reverend Call is quoted, “Uncle Nearest is the best whiskey maker that I know of.” Call reportedly said to Green, “I want [Jack] to become the world’s best whiskey distiller – if he wants to be. You help me teach him.” So, who was Nathan Green? Weaver started a research effort that now includes journalists, historians, archivists, archeologists, and geologists that have so far uncovered over 10,000 historical artifacts in six different states, and the collection is still growing.

For obvious reasons, little written record of the contributions by slaves in the early days of American whiskey distillation exist – few slave owners felt compelled to offer credit to those who they considered property. But we do see ads and bounties for runaway slaves who were considered valuable for their skill in making whiskey.

George Washington, one of our country’s first commercial whiskey makers, relied on six slaves and two Scottish foremen to make his profitable rye whiskey. In 1799, his distillery at Mount Vernon produced 11,000 gallons of whiskey, placing him among the largest whiskey distilleries in the country at the time. He even listed the slaves in his ledger as distillers. In 1805, future president Andrew Jackson took out an advertisement in regional newspapers offering a bounty for his runaway slave George, who he claimed was a “good distiller.”

The slaves honed their craft at the plantations where landowners often looked the other way, allowing slaves to make moonshine for their own use. In their eyes, it allowed the slaves to blow off steam on their day off – helping to keep them in line. Some of those slaves brought a critical skill with them from their West Africa homeland. The use of charcoal to purify food and liquids. By passing the rough spirits through charred wood, impurities were stripped from the liquid, producing a safer and more palatable spirit. Despite stories of the spontaneous invention of charcoal filtration by white distillers in the early 1800s, the slaves had been passing the technique word-of-mouth for generations.

It is the refinement of this technique by Nathan Green that resulted in the now famous Lincoln County Process, integral to Tennessee Whiskey production and taste. After the spirits are distilled, they pass through – or are steeped in – charcoal before being placed in casks to age. It is the filtration through charcoal, specifically charcoal from the local Sugar Maple trees, that made the Jack Daniel’s distillery unique.

But onto the man himself. Nathan ‘Nearest’ Green was born in Maryland(?) around 1820 into slavery. Little is known of his life (or when he died), but we do know that he was the property of firm known as Landis & Green in Lynchburg, Tennessee, and was likely hired out to Dan Call to help with his distillery. Many of the early Kentucky distillers relied on slaves to run their business operations; Elijah Craig, Henry McKenna, and Jacob Spears were all known to have used slaves to make their whiskey. Green could neither read or write, but he was an avid fiddle player and lively entertainer. Many believe his nickname ‘Uncle Nearest’ was a term of endearment, due to his warm and friendly demeanor. He married Harriet Green and together they had seven boys and two girls.

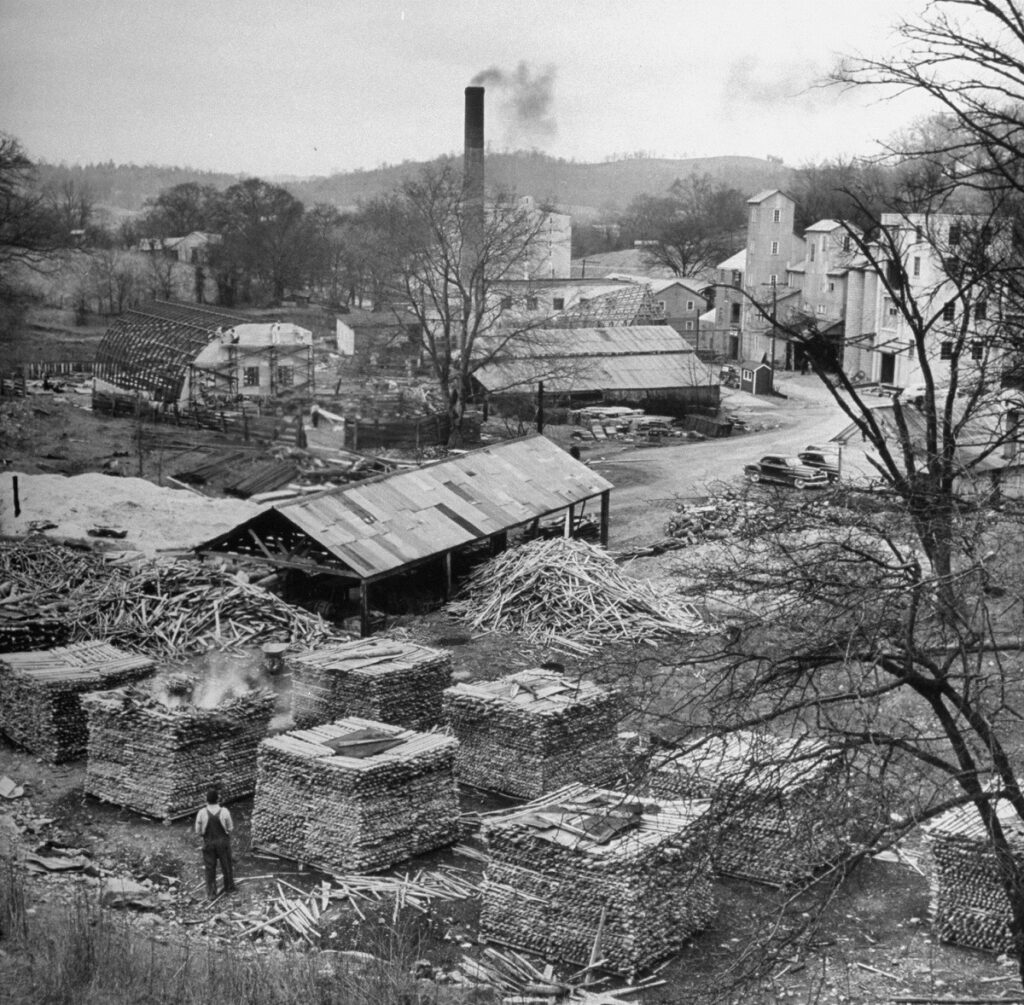

On January 1st, 1863, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring that all persons being held as slaves in the rebellious states be freed. On April 9th, 1865, the Civil War ended, effectively freeing all those still in captivity within the Confederate States. Uncle Nearest was a free man. But he decided to stay on at the Call farm and in 1866 his young mentee Jack purchased the distillery from the good reverend and established the Jack Daniel Distillery – the first registered distillery in the United States. He made Nathan Green his Master Distiller, making Uncle Nearest the first Master Distiller in the United States – black or white.

The whiskey sold well and made both men and their families wealthy – possibility making the Green family the wealthiest black family in Tennessee. It wasn’t long before Jack decided to expand and moved his distillery to a new, larger facility in Lynchburg. It was at this point that Uncle Nearest either retired – or possibly passed away, the details are still sketchy and grey – but he did not make the move to the new location. His family, however, stayed on with the company. His sons George, Eli, and Lewis all worked alongside Jack and his descendants. All told, seven generations of the Green family have worked in the Jack Daniel’s distillery next to descendants of Jack Daniel.

As Fawn Weaver and her army of researchers continues to uncover more of the story, she asked one of Nathan Green’s descendants what she could do to memorialize the legacy of the first Master Distiller. “Put his name on a bottle” was the response. And she did just that. In 2017 she created Uncle Nearest Inc. and opened the Nearest Green Distillery and began producing Uncle Nearest Premium Whiskey. It became the most award-winning American whiskey in both 2019 and 2020.

The Tennessee Whiskey company is America’s only major distillery owned by an African-American woman. The all-female leadership team – also the only example nationally – includes Victoria Eady Butler, Nathan’s great-great-granddaughter. She is the company’s master blender, and the first female African-American master blender in history. She is also the first Black woman to win the Icons of Whisky Master Blender of the Year award in February of 2021.

Overall, women make up about 30% of whiskey drinkers, but half of the consumers purchasing Uncle Nearest whiskey are women – propelling the company’s growth. They have created a company whose workers are half men and half women – echoing the population at large.

This is a story that has an amazing beginning, middle, and end. So, try the award winning Uncle Nearest 1865 100 proof or the 1884 small batch 93 proof whiskeys. Smooth and sweet, with a side of history.

Cheers!

Bill

AotCB-033

Instagram@architecture_of_the_cocktail

Previously in Architecture of the Cocktail:

Architecture of the Cocktail: Ten Things You Probably Didn’t Know About Bourbon, by Bill Stott

Architecture of the Cocktail: The True Story of Jack Daniel’s Whiskey, by Bill Stott

Architecture of the Cocktail: World Whisky Day. A Brief History of Whisk(e)y?, by Bill Stott

Architecture of the Cocktail: The Japanese Whisky and the Highball, by Bill Stott

Architecture of the Cocktail: The Delicious Dozen, by Bill Stott

Architecture of the Cocktail: What makes a cocktail, a cocktail? by Bill Stott