We tend to take ice for granted. Even our great, great grandmother’s and grandfathers had easy access to ice. But for most of human history, ice was only seasonally available, and even then, a luxury that most could not afford. The requirements for an alcoholic drink to be called a cocktail are that it contains a spirit, sugar, water, and bitters. Today we use the minimal dilution that ice brings to a cocktail during the shaking or stirring to provide the water, but in the early 1800s when the cocktail was first codified, it was simply water. In fact, the value of cooling drinks during the warmer months was greatly up to debate, with many believing that a hot drink was better when hot. That all changed in 1806 when a young enterprising New England businessman decided to sail up to the Arctic and bring ice south to the east coast and the Caribbean.

Prior to the beginning of the nineteenth century, ice was collected from snow and ice during the winter and stored for the summer months, but on a very modest scale. As far back as the Late Bronze Age (circa 1750 BC) Akkadian tablets show ice houses along the Euphrates River for storing ice, and similar efforts occurred in South America, Russia, and India. The ice was used primarily for cooling drinks, and available only to the wealthiest citizens.

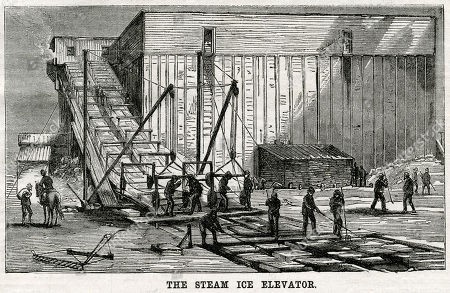

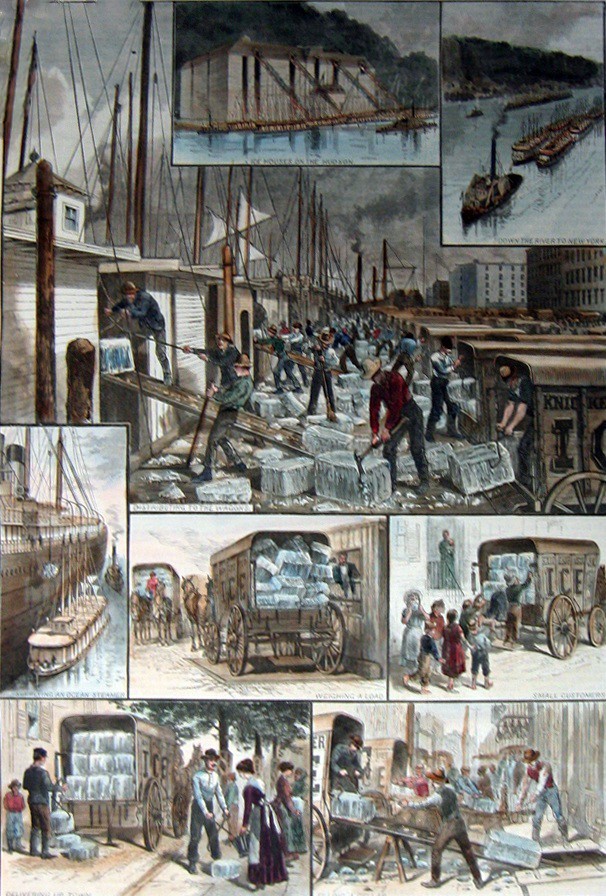

The Ice Trade, or the Frozen Water Trade as it was called, was started in 1806, by a New England entrepreneur named Fredrick Tudor, who went on to be dubbed ‘The Ice King”. He formed the Tudor Ice Company, and after several initial setbacks he successfully shipped ice to the island of Martinique in the Caribbean, looking to sell it to wealthy European businessmen. Through trial and error, he developed strategies to store the ice while onboard and built specially designed storage houses for the incoming ice. It was successful enough in the hot, humid summers that he quickly expanded to Cuba and the southern United States. Between the 1830s and 1840s the trade extended across the Atlantic to England and Europe, and eventually all the way to India and China. The largest growth, however, was the East Coast of the US, and extended deep into the Midwest thanks to the newly constructed Eire Canal. By the mid-1820s, 3,000 tons of ice was delivered annually to Boston alone, a city with only 50,000 inhabitants – or 120 pounds per person. Large American cities became the biggest users, and it changed how perishable items were stored and moved across the country. The meat packing industries in Chicago and Cincinnati were able to use new refrigerated rail cars to send their product deeper into the US. By 1847, almost 52,000 tons of ice was sent by ship or train to 28 major cities across the expanding US.

Ice, of course, completely changed the arc of the cocktail. ‘The Ice King’ would enter a new market and give his product away for free to the wealthy. He would arrive in a city and book a room at a boarding house. That evening at dinner he would bring a cooler filled with iced alcoholic beverages to the table and offer them around. Most thought it was a silly proposition – until they had their first drink, then they were hooked. After they had a taste for the chilled drinks in the hot and humid climates, he would then begin charging them whatever he wanted, knowing that once they became accustomed to iced drinks, they would never go back. In a way, it is not surprising that the US was the first to develop the cocktail. Being the first nation with a never-ending supply of ice, it was probably inevitable.

Prior to the availability of ice, drinks were served hot. Even in warm climates during the summer. The theory was, in the hot and humid summers people sweat, and the conventional thinking was that this was how the body rid itself of its excessive heat. Hot drinks caused you to sweat more, so this was even better. Probably an easier argument when the is no other choice. But when you could be handed a tall beverage filled with ice – a julip, cobbler, or swizzle – that old way of thinking seems less desirable.

Once ice became available, it started an explosion of new alcoholic drinks, primarily in the United States, but also around the globe. The Julep is one of the earliest American drinks, and dates to at least 1784. It was originally used as medicine, and it was thought to help cure stomach and throat ailments. John Davis records in his 1803 book, “Travels of Four and a Half Years in the Unites States of America” that a julip was a ‘dream of spirituous liquor that has mint steeped in it, taken by Virginians of a morning”. Once ice began to be included, it left the medicine cabinet and showed up at taverns and hotels.

Juleps and cobblers (named for the glass filled with small square ‘cobbles’ of ice) were sensations. The Sherry Cobbler, created some time in the early 1830s, inspired the first cocktail shaker – the cobbler shaker. It was such a sensation that Charles Dickens included it in his “The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit,” written in installments from 1843-1844.

“Martin took the glass with an astonished look; applied his lips to the reed; and cast up his eyes once in ecstasy. He paused no more until the goblet was drained to the last drop. ‘This wonderful invention, sir,’ said Mark, tenderly patting the empty glass, ‘is called a cobbler. Sherry Cobbler when you name it long; cobbler, when you name it short.’”

In the Caribbean, the swizzle became the hottest (no pun intended) drink in the West Indies. A rigid branch of the Quararibea Turbinata tree was traditionally used in cooking to mix ingredients together. When the Le Bois Lélé, or Swizzle Stick, is placed in a glass full of spirits, citrus, sugar, and crushed ice and spun around, it has the effect of super-cooling the liquid, not only making a smashingly refreshing drink, but by cooling the drink so quickly it slows the ice melt, and as a result the dilution.

And this, of course, is what all that shaking and stirring is about. A good shake is 12 to 15 seconds long, and a standard stir is 30 seconds (my timing – not everyone agrees). You might think that if you shorten the time in the shaker or the mixing glass you will end up with a stronger – less diluted cocktail. But the opposite is often the result. By cooling the drink completely, then placing it in fresh ice, the liquid is less likely to melt the ice in the serving glass.

And I know I just said this, but unless specifically called for, always use fresh ice. Always.

Cheers!

Bill

AotCB-031

Instagram@architecture_of_the_cocktail