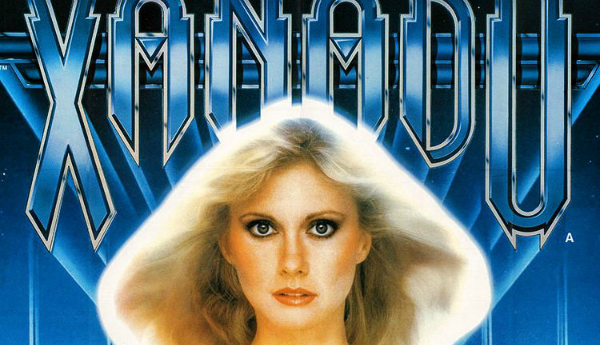

Ah, yes: the anticlimax to Xanadu. I saw it in the theater when it came out in 1980—as a joke, but still. What a tangled web of celluloid this clip weaves.

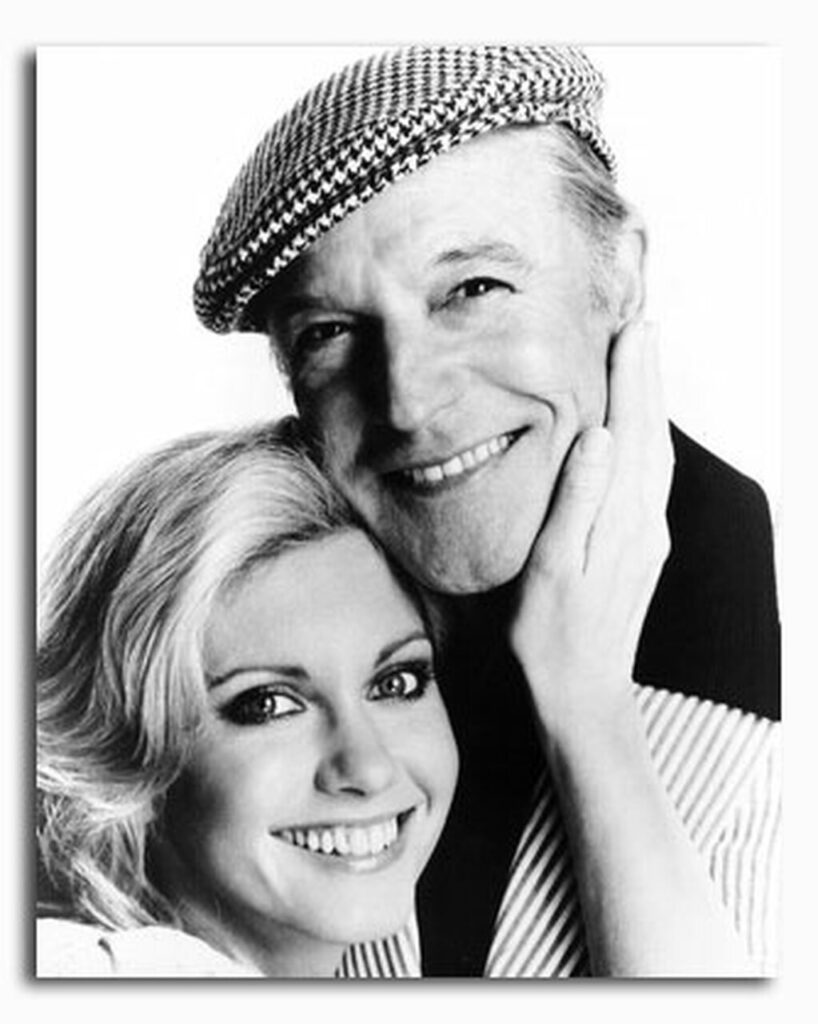

The movie was a sour maraschino on the glittering career of Gene Kelly—though, to be fair, his veneers never looked better. I’d like to think it was not desperation or necessity that caused the great hoofer to sign up for a roller-disco flick, but rather a chance to burnish his legacy and revisit his iconic skate-dance from It’s Always Fair Weather (1955). In fact, Kelly’s previous credit was as a grease monkey/second banana to the titular star of Viva Knievel! (1977), which may be the Hollywood definition of desperation (though he was at least billed above Red Buttons and Marjoe Gortner). It’s Always Fair Weather, downbeat and scuzzy looking, was a tired last gasp for the classic movie musical, but it had a certain ingrained confidence and professionalism that was the essence of the MGM brand. Xanadu doesn’t even believe its own magic.

Except when it comes to “Magic,” the sole surviving musical highlight of the film. Here, John Farrar crafted something actually kind of stately and mysterious, something almost transcendent—the closest the entire score comes to truth in advertising (for contrast, see ELO’s robotic, oxymoronic “I’m Alive”). It couldn’t keep Xanadu from torpedoing Olivia Newton-John’s film career, though. The path from Grease (1978) to Xanadu to Two of a Kind (1983) traces a sharp descending scale followed a seven-year rest, and then only ended by A Mom for Christmas.* But no harm: Olivia’s most mega pop hits lay just beyond the Reaganesque horizon. And “Magic” lives on, proving to be sturdier than any other aspect of the project. Just ask Martha Wainwright and Juliana Hatfield.

Jeff Lynne said he only did Xanadu to meet Newton-John, and I guess, in a way, working with her (to the extent they did) paved the way for his second career as one of the more consequential record producers of the past thirty years or so. Lynne also claims he never saw the movie, which makes one wonder who coached his bandmates through the pointless vamping that comprises fully half of the above six-minute-plus clip.

The director, Robert Greenwald, pulled off a reverse Riefenstahl here. Instead of making us believe what we shouldn’t, he makes us doubt everything we’ve ever known. Juggling mimes, zoot suits, skating ninjas, overenergetic background dancers, underchoreographed stars. Someone confused disco with a march and then added the pings of a syndrum, which do nothing to dampen the disturbing martial overtones. I’m haunted by the token shot of the token African American performers, suitably abashed, as if wondering how their music, any music, could be brought so low. Take a kitchen sink, throw it at the wall to see what sticks, and you’d end up with a more coherent product. Having been defeated by fiction (and logic, dancing, actors, scripts, continuity, and, oh, so much more) Greenwald has since become a successful—nay, important—maker of documentaries. What a world!

Given the imagined pedigree of Xanadu—the “plot” was lifted from the 1947 Rita Hayworth musical Down to Earth; Kelly’s Xanadu character of Danny McGuire has somehow been teleported from Cover Girl (1944), where he played opposite Hayworth—it’s a wonder its makers didn’t invoke the most famous speaker of the syllables “Xanadu” (and, coincidentally, a former spouse of Hayworth) and offer a role to Orson Welles. A blessing really, as he likely would have accepted. Maybe a number with the Tubes.

* Then there’s Sandahl Bergman, who danced down from the peak of All That Jazz (1979) to Xanadu to Conan the Barbarian and Airplane II: The Sequel (1982). Let’s be merciful and hold our peace on the peakless career of Michael Beck.

- Tom Fredrickson

Christopher Walken on Gene Kelly