Early medieval Christians took Lent seriously. No meat. No eggs. No dairy. Only one meal a day around 3 p.m., and that was a relaxation of not eating until evening. Pretzels, made with water, flour, and salt, were OK, but the Lenten diet was sort of like being a vegan with the exception of fish.

The season of sacrifice and penitence might have been more difficult for the aristocracy, who could afford to devote more land to livestock and therefore had more meat. Lent’s strictures might not have made that much of a difference in what commoners had on their tables. They could not afford to eat meat every day anyway. Food stores, including meat from animals slaughtered in early winter, likely were running low at this time of year.

Yet the folk found a few loopholes. The term fish also covered frogs, beaver tails, and barnacle geese (believed to have hatched from barnacles). If you were young, old, sick, or pregnant, you were not required to fast. One does wonder whether claims of illness rose during Lent.

And the self-denial did not affect only your diet. You were supposed to abstain from sex, even with your spouse (although the penance for the act was more lenient if you were drunk).

Modern-day Christians use Lent as a time to contemplate mortality and how they can do better in the time they have left. Early medieval Christians had mortality all around them. They lost half their children before age 5, and more than one-third of women died in their childbearing years. They heard about the afterlife constantly at Mass. And if they weren’t paying attention to the sermons, they need only look at the artwork within the church.

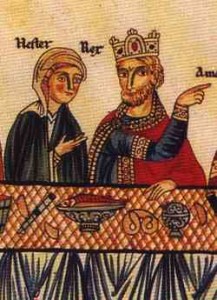

In my novel The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, Lent presented an opportunity to show how my recently converted heroine is still adjusting to a faith she knows little about. Sold into slavery, she and her children have been taken far from home, and Leova is still learning the language and customs.

About an hour before sext, Leova guessed, the front door slammed. She looked up from her inspection of the hearth and beheld Helewidis bearing a sack and a jug of wine. Without a word, the shrew sprinted to the bedchamber. The tightness at the back of Leova’s neck eased slightly. At least, Christians let the sick have wine during Lent, a concept she was still trying to understand. All she could grasp was that the Christian God dictated

that the sole meal of the day in the late afternoon have no meat, milk, or eggs. At this time of year in Eresburg, Leova would have been careful with the food because the stores would run low, but none of the gods ordered the folk to deny themselves. The goddess Erda merely asked for some stalks of rye to be left standing during the late spring harvest and tied with flowers, while other gods asked to share in the feasts at harvest and midwinter.

Leova visited the kitchen throughout the day and was pleased by what the cook had prepared for dinner: a soup with chunks of fish floating in the broth with cabbage and carrots. The bell for nones could not come soon enough. Leova and Sunwynn brought trays with bread, soup, and beer to the bedchamber, which smelled of the wine Helewidis had used to cook the lungwort spread on a small table near the hearth. Through the part in the drawn bed curtains, Leova spied Ragenard asleep, his face ruddy.

Helewidis pointed to the door. “Out, stupid slut!” She growled something else.

Most of the faithful knew little more than Leova. They lived centuries before the printing press, which meant illiteracy was the norm and books were so expensive they belonged only to the wealthy. They didn’t have Bibles to study and relied on the clergy. They followed the dietary rituals because that is what the priests told them to do to avoid any more days in purgatory or worse, spend eternity in hell. Yet these rituals must have also made Easter all the more joyous.

Kim Rendfeld is the author of two novels set in the early days of Charlemagne’s reign: The Cross and the Dragon (2012, Fireship Press), in which a young noblewoman must contend with a jilted suitor bent on revenge and the anxiety her husband will die in the coming war, and The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar (2014, Fireship Press), a tale of a peasant mother who will go to great lengths to protect her children after she has lost everything else. You can read the first chapter of either book, read excerpts of reviews, and learn more about Kim at kimrendfeld.com. You can also visit her blog Outtakes of a Historical Novelist at kimrendfeld.wordpress.com, like her on Facebook at facebook.com/authorkimrendfeld, follow her on Twitter at @kimrendfeld, or contact her at kim [at] kimrendfeld [dot] com.