As I suggested in my earlier post, conservatives have often drawn attention to the intertwining of government policies, political rhetoric and social standards. One important critique of the former structure of welfare policy is that it created a “culture of dependency”; in this critique sometimes it was the intention of social reformers and sometimes the unintended consequences of government policies, but poverty’s persistence was often blamed on the development of a culture that accepted, even encouraged, dependence instead of self-reliance. If this is the case, then is it not even possible that a culture can be developed that through the use of its prevailing metaphors makes violence more reasonable, acceptable, normal? There is at least nothing anti-conservative in the posing of the issue in this way, for attention to culture has long been a feature of a conservative critique.

Now, I am not sure I am persuaded by this argument. I find much to be admired in the jaunty defense of inflamed speech by Jack Shafer and the very thoughtful critique of it by Andrew Sullivan. But at least some of the difficulty is in the elastic quality of speech itself. If a reviewer claims she doesn’t like a book she has read because it employed a scattershot approach, she guilty of violent rhetoric? If a football coach says his team will use aerial bombardment to destroy the opposing team’s defense, is that inflamed violent rhetoric? If I say a scoundrel convicted in a political corruption case should be hung from the highest yardarm, am I calling for the public hanging of Tom DeLay? In each case I would think not.

But what about the political pundit who soliloquizes “Hang on, let me just tell you what I’m thinking. I’m thinking about killing Michael Moore, and I’m wondering if I could kill him myself, or if I would need to hire somebody to do it. No, I think I could.” That would be Glenn Beck. And finally, what about the candidate who suggests that “second amendment remedies” may need to be taken if an election goes the wrong way? Is that a metaphor? No, I really don’t think so.

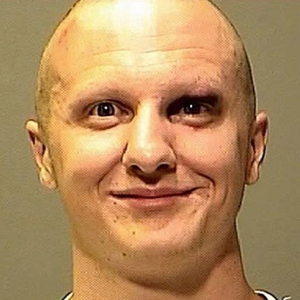

And that is what I find so increasingly odd about the whining in dismay by the right of any suggestion that their language might be a lens through which to interpret Loughner’s actions. The interpretation of the Second Amendment by the right and the reason for its strong defense of it is distinctly political. From this view, the Second Amendment is not a defense of hunters and the rural way of life, but the preservation within the people of a check against tyrannical abuses of their government. This rather quaint misreading of the classical republican anxiety about standing armies suggests that yes, guns are important not only for personal defense, but for the public defense of liberty. If then the current regime is anchored in fascism, socialism, Marxism, threatening liberty, then indeed the tree of liberty should be watered with the blood of patriots. Loughner then is perhaps to be dismissed as an inopportune buffoon a poor chooser of time and targets, but are his solutions not “second amendment remedies?”

– Lawrence Spaulding

.

More from Lawrence Spaulding:

On Wisconsin: Mr. Goose, Meet Ms. Gander by Lawrence Spaulding

Thoughts on Clearly Nebulous’ Query by Lawrence Spaulding

More (or Less, Really) on Words and Violence, by Lawrence Spaulding

Words and Actions, Words as Actions, by Lawrence Spaulding

On Political Writing and Reading… and Kinda Obama… by Lawrence Spaulding

Lame Ducks and Legitimacy, by Lawrence Spaulding

Will Progressives Treat BHO Better than Conservatives Treated GHWB?, by Lawrence Spaulding

.